– Jon Anderson

IT’S EARLY on Saturday morning and I’m up to watch El Classico, which is nothing short of the single-greatest regularly scheduled sporting event in the world. (If the NFL could contrive some way for the Seahawks and the Patriots to play every season, I’d be all for that.) F.C. Barcelona and Real Madrid possess between them the most dazzling array of soccer talent that you could assemble, and the game is worth watching simply to watch the artists at work, even if their work ultimately doesn’t result in the ball going in the back of the net. Soccer is nuance and subtlety, it’s chess on grass, with the beauty of the game displayed through quick moments and snippets here and there. I watch simply to enjoy these small moments of brilliance here and there, which were frequently on display at the Nou Camp this morning in what was, by El Classico standards, a generally disappointing affair: a moment of ingenious hold-up play from Suárez where he posts up a larger defender and traps a downward flying ball with his left thigh and drops it to his right foot, knowing exactly where his next pass is going to go before the ball has even hit the ground; a deft turn and spin from Busquets just above the 18, clearing the danger in the Barca defense and starting the play the other way; Iniesta, the world’s greatest passer, firing a laser beam of a pass through three defenders onto the foot of Messi and creating a chance; all of these crosses from the Real wings weighted perfectly, seemingly destined to find a teammate’s head that just hang there, drifting into the box and striking more fear into the Nou Camp faithful with every passing moment. All of these moments are beautiful, elegant and graceful while, at the same time, taking place within an activity which is feisty and tense, combative and fiercely competitive. There is no greater rivalry than El Classico given the history and national identity connected to the sides and given the talent at both sides’ disposal. I sit back and soak in all of these little moments in the game and enjoy them for what they are regardless of the outcome. It really is a beautiful game, an elegant game. The game is poetry in motion.

But for all of that maneuvering of the pieces around the chess board during the course of 90 minutes, for all of those individual moments of brilliance, you still need to get a result – and god damn it, it’s hard to do that.

And, naturally, this game turned on a mistake, as a 90th minute set piece from Real Madrid turned into something more resembling a jail break. Barca’s defense got it all wrong and Sergio Ramos equalized with a header – and if he hadn’t gotten to it, someone else would have, as there were five Real players open in the center of the box to meet the cross. It was a piece of abject and amateurish defending at the worst possible time from Barca which wound up costing them, as Real snuck out of the Nou Camp with a 1:1 draw. For all of the individual moments of brilliance, for all of the great build up play and link up play from Barca through the center of pitch, the second goal Barca needed to put the game away didn’t come, and then that one moment occurs and you shut it off upstairs and you don’t communicate and the ball is in the back of your net, the points Barca needing in the table to stay in contention for the title being wasted and going awry. Barca were the better team, but the better team didn’t win.

But this is what always happens in soccer. Barca were six points adrift of Real Madrid in La Liga when, if there was anything just about this stupid game, they would have been seven after last week, as they had traveled to San Sebastián and got positively bossed by Real Sociedad. The Txuriurdin were all over Barca, but they somehow managed to miss the target time and again (seriously how did they not score more?), and then Messi does one of his Messi things and Sociedad hit the woodwork twice and have a goal strangely called back and it ends a 1:1 draw, earning a point for Barca they most certainly did not deserve. And for Real Sociedad, a small club with a proud tradition that has often gone toe-to-toe with the Madrids and Barcelonas and more than held their own, this draw is a bitter disappointment. They deserved to win the match.

But soccer has little to nothing to do with what you deserve, in the end. Over the course of the season, the teams that finish at the top of the table steal these points here and there which often come to make the difference. They get draws when they deserve to lose, they get wins when they deserve to draw. The margins in the game are so thin that the difference is often one single moment of brilliance, one moment of defensive lapse, or even some ridiculous own goal. The bigger clubs with the deeper pockets will wind up necessarily moving towards the top of the table by the end, using those resources to stock up on players capable of creating those moments of brilliance and competent enough to lessen the potential for disastrous errors, thus tilting the balance of power in their favor, enabling them to steal points in those 50-50 situations. And you can understand how, over time, this apparatus works. You can see how, during the course of a 40-game season, this will play out, but in the moment, of course, when one single match comes undone and the result winds up feeling unjust, the beautiful game feels incredibly cruel. Soccer is a game that, one way or another, always seems to find a way to break your heart.

* * *

So the results can be unjust, but we can deduce that the best teams win out, at season’s end, partially through the amassing of many unjust results in their favor. But at the same time, the unjust results can seemingly go against even the bigger clubs: witness Saturday’s El Classico where, in my opinion, mighty Barca were the better team and the better team didn’t win. I’m always amused by the idea that the bigger clubs in Europe float from time to time of forming some sort of Super League in Europe where the best clubs would play each other all of the time? Wouldn’t that be great?

Well, sure, it would, at first, but then the novelty would wear off really quickly for a number of those clubs and their supporters, and would do so for a very good reason: they would start to lose. Sports are a zero-sum game, after all. Someone would necessarily lose, and necessarily finish last. The structure of the game is fundamentally unfair, a self-perpetuating cycle in which winning begets you bigger prizes and purses, which you can then turn around and spend on better players and better coaches and the like. With those spoils, over time, have come a galling sense of entitlement among the game’s élite, a level of condescension implying that simply by the name on your jersey, you should just be able to show up and garner the spoils.

UEFA has constantly kissed the big club’s asses in the rejigging of the Champions League, a cash-cow of a cup competition which, to put it bluntly, isn’t really all that good, as it’s a bunch of extra games stuffed into midweeks during a season that’s already long and draining. For all of the pomp and ceremony and self-importance of the competition, the games are often dreadful. We’ve been told we’re supposed to care about it, but none of the Champions League Finals that I’ve watched have been particularly memorable. Most of the time, in fact, the better team doesn’t seem to win. Indeed, the ‘winner’ of today’s 1:1 El Classico draw – Real Madrid – have won two of the past three Champions League Finals, winning both times against sworn enemy and crosstown rival Atletico Madrid while managing, over the course of the 90 minutes, to look second-best on both occasions, only to push the game into extra time on both occasions and then carve out a victory.

And we hate it when Real Madrid wins. The next best thing to seeing your team win is seeing your fiercest rival lose, and Real Madrid is a fierce rival to everyone, owing to their phenomenal success, their Franco-fascist roots, and their constant back room and board room drama. Of course, most of the discreet, ineffectual, leftist bourgeoisie who root for Barcelona choose to conveniently overlook their own team’s warts, be it getting nabbed for signing underage players or the fact that there have been a seemingly endless string of tax evasion charges dogging the club’s players. We cherry pick and choose the facts in order to suit our narratives. Most of it just comes down to jealousy, of course – the act of wishing that a team you support could be better than another who always seems to win all the time at your expense. And while there were plenty of blue and red stripes on display in my footballing-mad neighborhood this morning, while nary a white jersey could be seen, Real Madrid wouldn’t be the biggest club in the world if nobody liked them. Just as there are shy Tories, there are shy Madrileños out there as well, people who don’t want to admit it because liking Real isn’t cool.

But we love it when Real fails. (Though it doesn’t happen often.) We love it those bloated bombasts who always buy their way to the top of the table stumble and bumble and fall. There is seemingly no end to the schadenfreude in Britain right now for the comedic stylings of Manchester United, a club which has gone through three coaches and spent over $600 million on players in the past four seasons but who, at this moment, is currently looking up in the table at West Brom. A particular venom is reserved for the ‘new money’ clubs – clubs like Chelsea and Paris St. Germain and Manchester City who weren’t any good until they got infused with massive amounts of petrostate financing, and who are now élite powers of the game, or a club like RB Leipzig, who currently reside at the top of the Bundesliga and who didn’t even exist until seven years ago, when Red Bull up and decided to dump a tonne of euros into the act of inventing a championship-caliber German football club. The idea of coming in and winning at the game simply by throwing a whole bunch of money flies in the face of the traditional/stereotypical narrative of the game, which is that these great clubs were of small and modest means when they were founded and grew to become giants over time entirely owing to their brilliance on the pitch. The truth is, of course, much more complicated than that. Chelsea and Man City have been around for over a century: they just weren’t very good for long periods of time. The backstory of they came to be good doesn’t really matter that much, in the end, if they didn’t get the results between the lines. You can have all of the resources at your disposal that you wish, but if you don’t know what you’re doing, you wind up like Man U and go about pouring $600m down a rathole. And most of the football supporters who want to tout their club’s humble, modest roots only do so when it’s convenient, but their clubs time and again act out of their own self-interest when wider issues crop up, and do so at the expense of clubs whose roots are just as humble and modest and who are still humble and modest to this day. It’s an unfair game, one between the haves and have-nots in which the haves want to do everything to keep it that way.

But knowing all of that, I still root for Barcelona. I admit it. Like most fans, my footballing rooting interests are tiered and complicated and sometimes run in conflict: big teams that we like, but also smaller clubs as well. I like Barcelona because I’ve always liked the way they play. Among the large British clubs, my life ethos seems to align more with Liverpool than any of the others. My love of Norwich City is well-documented, of course, and it excites me that the latest incarnation of the team which first got me interested in soccer decades ago, the Seattle Sounders, will be playing for their first MLS Cup a week from now. With each club comes a different set of expectations, a different definition of success. But in each case, that sense of being wronged by the unjust result feels the same. You curse the stupid fucking game and wish that it didn’t hold your attention. How can you like something in which seemingly so often, you feel as if fate or the moon or the stars or the forces of evil or the goddamn refs or those moving goalposts all conspired to deny your team the result that it deserved? There is no justice in this game. The bad guys always win.

Except, of course, when they don’t.

* * *

We watch the biggest clubs because we want to see the game’s greatest stars. I thought I would get the chance in person to do that this past summer, during the Copa América Centenario, as some good fortune in the draws had brought those of us here in the Bay Area a really great slate of games to take place down in Santa Clara at The Pants. Alas, it turned out to be something of a disappointment on the star front: neither Lionel Messi not Luis Suárez played, as both of them were still injured; James scored and ran the game for Colombia and generally made Klinsmann’s USA FC look stupid for an hour, but then he injured a shoulder and had to leave the game.

The one great star turn that I did get to see, however, was that of Alexis Sánchez, when Chile took on Mexico in the Quarterfinals. The Chileans moved Alexis to the left side, in order to attack a weak right flank of the Mexican defense, and after Alexis roasted the Mexican right back on his very first touch, making him look like he was standing in cement, the Chileans then took to running the entirety of their offense through Alexis. Every attack begin with a ball to Alexis down the left. And Alexis was brilliant. He was absolutely brilliant. I don’t think I’ve ever seen, in person, someone play a better game of soccer. His touches, his movement, his passes were all elegant and effortless and perfect. His name doesn’t appear on the scoresheet enough to suggest how dominant he really was. Alexis essentially set up five goals all by himself while his grateful teammates went about divvying up the spoils.

The final score of the game was ridiculous, in the end – Chile 7:0 Mexico. The mass of El Tri fans assembled at The Pants went, over the course of 90 minutes, from loving their team to hating their team to a sense of something akin to begrudging gratitude, coming to realize that they were present for a master class in the game because Chile were so good that nothing the Mexicans wanted to do would have even made a dent.

And part of what made it so surprising, of course, is that it was Chile doing this. Chile are now the 2-time defending champions of the Copa America after this summer, despite the fact that, in comparison to other South American sides, they have considerably less talent at their disposal. Not no talent, mind you. I was explaining to one of my friends, at the start, who their best players were and saying stuff like “that guy plays for Arsenal, and that guy plays for Bayern Munich, and that guy plays for Barcelona,” and the name-dropping of such clubs certainly resonated with a soccer-viewing neophyte. It’s just that their roster pales in comparison to that of Argentina and Brazil and even Colombia. But the Chileans are a case of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts – something born through experience, as the core of their team have been playing together in national team settings for more than a decade.

And long before Alexis was living in London and playing for Arsenal and winning a pair of Copa Americas, he and some of his future Chilean national teammates were plying their trade in a place about as far removed from the bright lights as you can possibly get – at Club de Deportes Cobreloa in the city of Calama, a mining town in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. Cobreloa are a small club but also a proud one, having won five Chilean titles, and its also a club with a propensity for developing surprisingly good players over the years. But when you’re a small club, whatever successes you achieve can be difficult to sustain, if not impossible. Bigger clubs come calling when they know you have great players, curious if you’d like to sell – and how can you not sell, seeing how a big transfer fee can prop up your budget for the entire year?

And the other reason you should sell is that the player will most likely want to go. In the case of Alexis Sánchez, he was sold from Cobreloa to the Italian club Udinese – another modest club known to have a keen eye for talent. Udinese loaned him out twice, first to Colo Colo, the biggest club in Chile, and then to River Plate in Buenos Aires, who are one of the biggest clubs in South America. He then played three years with Udinese in Italy, was sold to Barcelona after three seasons, and sold to Arsenal after that. This sort of meandering journey isn’t uncommon among even great players. In fact, it’s pretty normal. You bounce around, you move from club to club, there are ups and there are downs – and sometimes the downs can seem like down-and-outs. Jamie Vardy was playing in England’s 5th Division and working in a factory. Dmitri Payet was selling shoes. How on earth is it possible that someone who can do stuff like this was selling shoes?

|

| Just stop it already, Dmitri |

|

| OK, now you are just showing off |

Payet now plays for London’s West Ham United, a club with bigger aspirations than they are presently capable of pulling off. In the endless strata of soccer, which stretches from the glitzy and glamorous clubs at the top of the pyramid down through endless divisions and state leagues and regional leagues, clubs of all sizes eventually sort themselves out and find their own comfort level. And the fans of the club come to adjust over time, of course. The fans at every level of the game come to understand the limits of their favorite club’s exploits. It doesn’t mean they’ll necessarily like it, of course – most every conversation I have with Norwich City faithful inevitably harkens back to the club’s golden age, which stretched from the mid-1980s until they were relegated from the EPL in 1995, during which time they were one of England’s best clubs. But we members of the Yellow Army all have come to understand that such a terrific run, in this big-money day and age, is nearly impossible. Norwich doesn’t have the means to compete. It’s not a big club. You come to measure success in different ways: maybe it’s in the 1-off match against a bigger club where you get the better of them; maybe it comes from seeing a former player go on to do great things, knowing that your club contributed to the advancement of his career.

But that’s all big picture shit. In the moment, the fact is that I dragged my ass out of bed 38 times during the 2015-2016 EPL season for kickoffs at 4:45 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. and fuck-its-early-a.m. and had to keep myself from cursing aloud, lest I wake up the Official Swansea Fan of In Play Lose, who was wisely sleeping in while I was seething at 38 games of general Norwich City incompetence. “Jesus christ, could you mark the damn center back on the corner!” “How could you miss that? It was a sitter, god damn it!” *grumble grumble bitch moan seethe*

Small club? Modest means? Fuck that. I want to win, damn it.

Sure, it’s nice to see Norwich City guys excelling at other clubs, or see two of them teaming up for a great goal in the Euros, and I suspect the could will sort out their current problems and find their way out of Div. 2 and back into the EPL eventually. But at that point, they’ll probably get smacked back down again, because this is how it goes. There isn’t really any point in having expectations of success, of having delusions of grandeur, since those sorts of fairy tales never come true ...

* * *

After El Classico ends, I flip through some highlights of Saturday’s games in the EPL, one of which is taking place at the wonderfully majestically named Stadium of Light in Sunderland. Sunderland won today, which for them is sort of amazing. They’ve been abjectly terrible for the past few seasons, pulling off a Houdini act each successive spring to avoid being relegated. The club is now for sale, yours for the taking for a cool £170 million. A deceptively low figure for a Premier League club, since one of the things you’ll be assuming, should you decide to buy, is the club’s £140 million in debts: a consequence of trying to compete at the game’s highest level for years, and failing rather miserably at it.

There are basically three tiers-within-the-tier that is the top flite of English football. There are five clubs on top owing to pedigree and bank balance: Man U, Man City, Chelsea, Arsenal, and Liverpool. There is a second tier full of hopefuls from the big cities striving to compete with their rivals across town: Tottenham, Everton, West Ham, Crystal Palace. And then there is everyone else, whose best hope is to break into the Top 10 and maybe land a Europa league spot. Sunderland are most definitely in the ‘everyone else’ category, as were their opponents today, a modest club from a smaller city doing what they usually do, which is hover right around the drop zone at the bottom of the table.

Except unlike the usual assortment of modest clubs from smaller cities hovering right around the drop zone, this particular opponent’s struggles of late – including losing 2:1 today at Sunderland – are worth noting, because the losing club today at the Stadium of Light was Leicester City.

What’s happened to Leicester? Quite simply, after beating the 5,000-to-1 odds to win the EPL title a season ago, the Foxes have regressed to the mean. When you win the Premier League, all of your tactics and technique get dissected and scrutinized over the summer and, as such, the Foxes tactics no longer hold the element of surprise. Factory-worker-turned-England-striker Vardy, after scoring goals for fun a year ago, has suddenly lost his Midas touch and seemingly can’t hit the ocean from a boat. And then N’Golo Kanté, the Foxes’ most important defensive player, was promptly sold to Chelsea for £32 million. A shrewd business move, of course – they’d paid €8 million to pry Kanté away from his French club – but one which reinforced a hard truth about the Premier League, which is that in spite of the big infusion of cash that comes from winning the EPL and doing well so far in the Champions League, clubs like Chelsea will always have more of it. Leicester still is, for all intents and purposes, just another small club from a small city.

And bless them for that, along with Norwich City and Udinese and Real Sociedad and Club de Deportes Cobreloa and all of the others, because it’s the small clubs which are the heart and the soul of the game of soccer. The small clubs don’t have the luxury of throwing away hundreds of millions of dollars or euros or sterling or any other currency. The small clubs beat the bushes and comb the back roads for players, they buy low and sell high, they develop and promote from within. You cut your teeth at the small clubs, you learn the realities of the game there. Small clubs develop young players and grant second chances to those who fall from grace. The small club’s fans are patient, supportive, and passionate about the club – a far cry from the assortment of bandwagon jumpers flocking to the flavors of the month at the tops of the table. Small clubs are ingenious, imaginative, resourceful and tenacious, doing more with less and, every now and then, getting a good result here and there.

Or, in the case of Leicester City, you pull off the impossible. Dreams can, in fact, come true. Leicester’s EPL title this past spring was a triumph for the game as a whole. It brought back the romance, it decreased the cynicism, it shook things up and shook out some of the cobwebs, bringing some freshness to a game which had ultimately become rather predictable and stale with the same small group of clubs winning everything all the time and constantly going about remaking the rules in their favor. Leicester has captured the imagination of fans across the globe.

How are Leicester doing this season? Who cares? Everything they might accomplish this season is an extra helping of gravy. Leicester carved out a place for themselves in the history of the game like none other. They don’t have to win 20 titles to be remembered. All they had to do was win one, in this era, under these circumstances, to remind people that it’s possible for a small club to do. It is unlikely? Absolutely. Is it hard to do? Absolutely.

And if we’re being honest here, the same sort of critique I offered previously about Real Madrid applies to Leicester as well. If winning titles in soccer is ultimately determined by stealing a good number of points that you don’t necessarily deserve, then a title winner with Leicester written on the jersey is just as likely to benefit as one with Bayern or Barca or Real. I can think of two such unjust results in their favor off the top of my head – both the games with Norwich. The Foxes took all six points from those two games, which was about five points more than they deserved. After taking the league by storm in the first half of the season with a wild, open, attacking style, the Foxes had a seemingly endless string of 1:0 wins and come-from-behind draws after Christmas. Now, when you’re a bunch of nobodies, it’s easy to call this ‘riding your luck,’ but it’s no different than what Real and Barca and Bayern and the like do with regularity. What we see on the fronts of the jerseys changes our opinions of the performance when, in fact, what Leicester did, day to day, was no different than what any other league winner does from day to day. It’s still a cruel game, and Leicester knows plenty about the cruelty of it (most notably this madcap ending to a Div. 2 playoff against Watford in 2013) but for a season, at least, cruelty felt fit to rear its ugly head in some other city.

And it’s interesting to see how quickly this has changed the consciousness of the footballing fan. Instead of looking at a small club punching above it’s weight as a fly by night, you start to think, “could this be the next Leicester?” On Saturday in Italy’s Serie A, perpetual champion Juventus defeated Atalanta 3:1, but the fact that Juventus had to actually take Atalanta seriously was actually the story of the day. Who the hell is Atalanta? They’re a smaller club from Bergamo that have been rampaging along in Serie A of late, moving within striking distance of the European places with a roster composed mostly of young players that appears to be coming good. But how good? Good enough that you can’t help but wonder if Atalanta is … dare we say it … the Italian Leicester in the making?

And now small clubs everywhere want to think of themselves as the next Leicester, and you know what? Good for them. If Leicester can make some history, then why can’t they do it? Leicester have set the bar impossibly high, of course, accomplishing what seemed to be unthinkable, but for the next club that reaches those heights – a question of when, in my mind, rather than if – it will have been a most remarkable and exhilarating of journeys.

***

I hadn’t given Atalanta Bergamo any thought at all until I noticed, not too long ago, that they were high in the Serie A standings. When you follow the international game, you will occasionally take a glance at the tables in the other leagues, curious as to who is doing well (or, in my case, who is doing really badly, since this is In Play Lose, after all). I’ll look at the table in all the big European leagues, and maybe also in some of the lesser ones as well, just so I can get a sense of what is going on. When you do that, of course, you usually see an assortment of familiar names at the top of the table. It’s a lot of the same old same sold. Sporting or Benfica or Porto are winning in Portugal, Ajax or PSV or Feyenoord are winning in Holland, blah blah blah and there’s nothing much to see here. What occasionally piques my interest is the name of some weird team that I’ve never heard of, but usually there’s a reason that I’ve never heard of the weird teams: they aren’t very good, and usually they’re trawling about the dregs and on the verge of disappearing once again into Division 2 oblivion.

And I was looking through the table a week ago for Brazil’s Serie A, a league I only casually pay attention to, and I came across a name of a team which I’d never heard of: Chapecoense AF. Who on earth are these guys? Whomever they are, they appear to be having a nice season: 52 points, in 9th place in the table, slotted high above quite a number of the Brazilian teams that I do actually know something about, but Chapecoense were a club I knew nothing about at all.

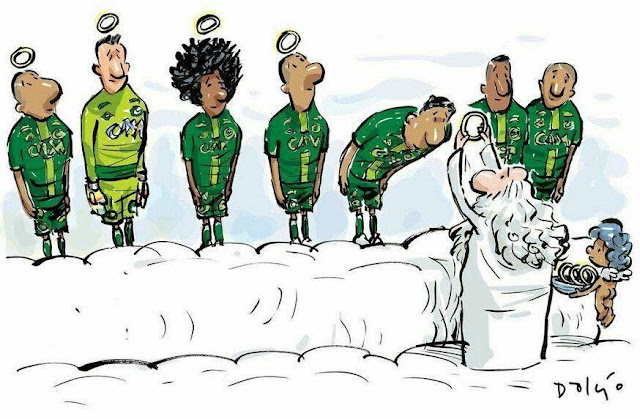

Well now I do, and given the way that knowledge came to pass, I’m wishing very much that I didn’t, because on Monday, the plane which was carrying the members of the team, the team’s staffers and executives, and a number of Brazilian football journalists to the first leg of Chapecoense's Copa Sudamerica final against Atletico Nacional, crashed in the mountains outside Medellin, Colombia, killing 71 persons.

And it was after the crash that the story of Associaçáo Chapecoense de Futebol came to be known to the footballing and sporting public outside of South America: Chapecoense were, in many ways, the Leicester City of Brazil. It’s a small club from a small city, Chapéco, a blue-collar city of meat packing and prospecting with 200,000 residents located near to the Argentine border in the south of the country. As recently as 2009, Chapecoense found themselves in Brazil’s Fourth Division, but they’d made a steady and stunning rise into the top flite of Brazilian football, being promoted to Serie A in 2014 and continuing their climb ever since, making their way into the top half of the table while battling it out with some of Brazil’s most legendary clubs. And as they were doing that, they were also competing in the Copa Sudamerica, CONMEBOL’s equivalent to the Europa League, and continuing to progress through the tournament, beating two Argentine clubs in the quarters and the semis to reach the Cup final. It’s a remarkable run, a fairy tale run from a club that no one could see coming.

And in the cesspool that is Brazilian domestic football – the game so awash in corruption and rot that the fans have stopped going to games and the players all flee to other parts of the world as soon as possible – the rise of Chapecoense was a breath of fresh air. Like many small clubs thrust onto big stages, they make friends wherever they go. Chapecoense were admired for their tenacity and resourcefulness, for doing more with less whereas so much of the game’s resources have been squandered within the nation over the years. Their rise piqued the imagination, proving that even the little guy could have their day in the sun and get their just deserts. And with a small town club comes a small town atmosphere. Instead of the typical sort of big city disconnect, where players keep to themselves and disappear behind fences and walls, all accounts seem to indicate that Chapecoense’s players felt a comfort in the city of Chapéco, whose residents weren’t just fans of the club, but had come to be seen as friends.

And now, it’s all gone.

|

| #forcachape |

You’ve really done it this time, footballing gods. Yours is a cruel, cruel sport, one to which many people dutifully enslave themselves regardless, but this is your cruelest trick of all. Damn you.

I’ve struggled to come to terms with this tragedy, not wanting to write yet another obituary in a year that seems particularly cursed, one in which so many of the people who’ve made an impact in my life have passed away. And yet, I felt compelled to say something, say anything, even though what I’m saying might make no sense at all. Football lost some of its greatest friends on Monday. Sport lost some of its greatest friends. Indeed, life itself lost some of its greatest friends.

We want to think of sport as being separate from life. We want it to be a diversion and a distraction, a chance to lose ourselves for a little while. But sport is not separate from real life. It is a part of real life. No game ever created more mirrors real life than soccer, a game in which the results are often unjust and sometimes the best that you can hope for is to scrape out a draw and come out even. It is a simple game which is complex and nuanced, laden with gray areas. The games if financed by, and profited from, capitalists with enormous wealth and little connection to the common man, while its labor pool are culled mostly from the poor and the immigrants and the working classes – commoners, ultimately, much like the commoners who follow the game with fervor. Soccer is life, in fact, and much like the rest of life, you want to see the good guys get ahead and win a little bit from time to time.

The investigation will take months, but early indications are that the aircraft, stretched to the outer reaches of its range, ran out of fuel. If so, it makes it all the more senseless and needless, bringing an outrageous negligence into play. This didn’t have to happen. This didn’t need to occur.

And I don’t know what to say about this. I’m at a loss for words. The words I know are useless, they know they are useless and they just give up and wander away.

The most heartbreaking image of all was that of the remaining Chapacoense players – those who were injured and couldn’t travel – sitting in the locker room at their home grounds where, a week earlier, there were scenes of wild jubilation after the club had qualified for the Cup final. Three players in total, looking lost in an empty room, having just been told that their teammates, their coaches, their bosses and everyone associated with the club were now gone in an instant.

And what’s struck me the most personally about this is the loss of those journalists traveling to cover the game. I get very upset when journalists are killed while during the course of during their jobs, because I’ve been a journalist for most of my professional life. These are my brothers in arms who have fallen. I take their loss personally. It’s been incredible to listen to numerous reports about the tragedy presented to the world by Brazilian sports journalists, all of whom have lost a friend or a colleague, yet all of whom are doing their jobs and their duty of reporting the news in a situation where most anyone else would want to run away and hide and not talk to anyone. It crushes me to hear their voices. It breaks my heart.

What do you say about this? What are the right words? I ask this because, in the ensuing few paragraphs, I will speak to the future of the club. This in no way is intended to be cold or dismissive of the suffering of the families who lost loved ones. We must control that which we can control, and there is no controlling what has just occurred. I’m not sure how to speak to the grief, the suffering of those affected. I really can’t find the words.

It takes decades to recover from something like this, if you ever really recover at all. Torino F.C. were the greatest team in Italy, if not Europe, in the late 1940s, winning five consecutive league titles and employing the bulk of the Italian national team. The entire team was killed in a plane crash in 1949, an incident which so shook Italian football that the national team chose to take a boat to the 1950 World Cup in Brazil, and Torino F.C. have never been quite the same since, winning on a single Serie A title in the 67 years since. More recently, in 1993, a plane carrying the Zambian National Team crashed off the coast of Libreville, Gabon, on its way to a World Cup qualifier in Dakar. The Chipolopolo were a rising force in African football at the time, having called attention to themselves by crushing Italy 4:0 during the Olympic games, but the national side vanished into obscurity for the next 19 years before pulling off a stunning win in the final of the CAF African Cup of Nations in 2012 – a game which took place in Libreville, Gabon, mere yards from where their compatriots’ plane had crashed 19 years earlier. Chapacoense will regroup and will go on from here. Whether they have any success at all is hard to say – but then again, success is never a guarantee regardless of circumstances.

And in times of tragedy, you often find that you have more friends than you may have realized. The outpouring of support from around the game worldwide continues. It’s a huge game that spans the globe, and yet its still inherently a small and tight-knit community. Most every Brazilian playing abroad speaks with a heavy heart, knowing of someone who was lost in the tragedy. In South America itself, Atletico Nacional, who were favored to beat Chapacoense in the Copa Sudamericana, have said they want no part of it, urging CONMEBOL to award the trophy to their fallen Brazilian opponents as a way to honor their legacy. Whether this will be done or not remains to be seen, but it feels like the right thing to do. (Update: Chapacoense will apparently receive the title.) Other Brazilian clubs have offered to loan players to Chapacoense, and there is talk of exempting the club from possibly being relegated for the next three years as it attempts to put itself back together. And amid all of this, Chapacoense still have one game left to play in the Brazilian season, a home match against Atletico Miniero of Belo Horizonte, even though the club has nothing left save for a handful of grieving players left behind. It doesn’t have a coach, it doesn’t have much of a training staff, there is nothing left.

But they should play. They should play, and they should give the fans in their grieving city a chance to gather, to honor the fallen, and to celebrate their memories. No player would ever want a game to be cancelled on their accord. The game should go on. In order to play the match, Chapacoense will have to cobble together a side, fielding youth team players and loanees along with those who were left behind, but who really cares who plays and what the final score will be? The result itself won’t matter.

They should play the game because it is still a beautiful game, one filled with beautiful moments here and there which, when stitched together, can be magical and memorable. It’s football which had brought all of these people together in the first place, and football will be what brings them together again. And for 90 minutes against Atletico Miniero, those gathered in the stands who have been grieving can instead focus their attention on what’s going on in between the lines, bemoaning a missed defensive assignment leading to a goal or a squandered opportunity on the offensive end – all of those little things which mean nothing in life’s broader context but, during those 90 minutes, come to mean absolutely everything. And when Chapacoense rebuilds, the club’s future will undoubtedly include quite a few matches in which they outplay the opposition, only to have to settle for a draw or maybe even be saddled with a loss. Unjust results in a cruel, cruel game? Perhaps you might come to see it that way. Or perhaps you’ll come to see the results as inconsequential, with the fact that the games are taking place at all, and coming to mean so much again to the players and the people, representing something more akin to an unbreakable winning streak.

#forcachape!